July 19, 2012

Previously I had read Victoria Hislop’s book, The Island. Like The Island, this book spans several decades. Both books tell the lives and history to a listener, a young person from the modern day Greek Diaspora who has returned to Greece. Both books are riveting reading.

Previously I had read Victoria Hislop’s book, The Island. Like The Island, this book spans several decades. Both books tell the lives and history to a listener, a young person from the modern day Greek Diaspora who has returned to Greece. Both books are riveting reading.

The Thread is the story of turbulent twentieth century Greece, centred on Thessaloniki and is told in the lives of several women, especially Katerina who by the time the book opens, is an elderly lady. It is a story of population movements, ethnic cleansing, famine, war, corruption, dictatorships and the lives of women in a very conservative society. It is also the slow burning love story of the relationship between Dimitri Komninos born in Thessaloniki in 1917 and Katerina Sarafoglous, a relationship that encompasses some of the most traumatic events in Greece of the 20th century.

-

Olga Komninos – a trophy wife of a very rich business man who has sacrificed his humanity for wealth creation. Olga’s lot is not always a happy one.

-

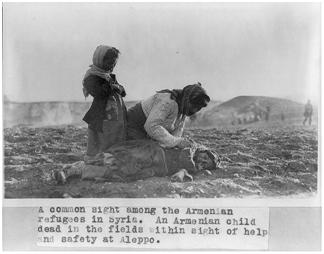

Eugenia – a refugee from Smyrna who adopts Katerina when Katerina is separated from her mother during the Greek evacuation of Smyrna in 1922. Eugenia is able to support herself, her twin daughters and Katerina by rug making.

-

Rosa Moreno – a talented seamstress working for the family business. Her family are shipped out of Thessaloniki with most of the Jewish population

-

Katerina – this is Katerina’s story, Katerina is a talented needlewoman and survives some of the most testing times in Greece because of this skill.

The terrible legacy of 20th century Greece emerges, a legacy that Greece has bought with it into the 21st century, and that is the legacy of greed and corruption. Katerina is tricked into marrying the repulsive Gregorias when she is led to believe that Dimitri, her true love, is dead. Gregorias has made his money from collaborating with the Nazi occupiers, his worst crime is to conspire to seize the Moreno factory after the family is deported to Poland. The other legacy is political fragmentation: the left and right are separated on the extremes and nothing can bring them together. And then one wonders, is the Greek legacy actually something that has been bequeathed to them by the Ottoman Empire? This legacy of corruption and greed, the military dictatorships and the failed state. If so, is this not also the legacy of other countries that have emerged from its shadow – Syria, Iraq, Albania, Serbia, Egypt, Libya, the Arab states, Morocco, Algeria. Maybe what we see in the Arab Spring is in fact the child of a collapsing and degenerate Ottoman Empire. The modern, democratic state asks that its citizens work together for the common good, the Ottoman Empire was a empire where its citizens were obliged to extract as much as they could for themselves for the State was not there for them.

Surprising facts:

-

Tobacco is grown in Greece

-

Greece (or Hellas) did not exist before the 1821 Revolution. Before then, what we know as Greece was part of the Ottoman Empire.

-

Greece has a silk industry

-

Women did not get the vote in Greece until 1952

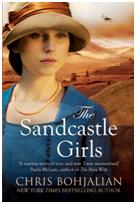

up the road from home. Now reunited with my keys, Monica and I headed back to the show for a well deserved cup of tea and as it was not raining to visit some of the stalls and gardens that we had missed due the pouring rain. One of the gardens was this one – a fantasy community garden where all the materials (or most of the materials used) are second-hand. Quite a revelation in this materialistic age. And I bought the book – and got free copy of the magazine thrown in. I did have some strange idea that I would justify buying the book because it would be a present for someone but the way it is going I am keeping it for myself!

up the road from home. Now reunited with my keys, Monica and I headed back to the show for a well deserved cup of tea and as it was not raining to visit some of the stalls and gardens that we had missed due the pouring rain. One of the gardens was this one – a fantasy community garden where all the materials (or most of the materials used) are second-hand. Quite a revelation in this materialistic age. And I bought the book – and got free copy of the magazine thrown in. I did have some strange idea that I would justify buying the book because it would be a present for someone but the way it is going I am keeping it for myself!

What are the dividing lines between Catholic Christians and secularists? Eco (author of Name of the Rose) and Cardinal Martini (in the Catholic corner) discuss four issues: abortion, why women cannot be ordained, hope and the future of mankind and the basis of ethics. Perhaps not the burning issues that many today would think need to be answered, but this book was written in the context of the impending millennium where some predicted this would bring in the end of civilisation as we know it. Today the burning issues would be child abuse, homosexuality, Darwinism or even the environment. Perhaps another age (not too long ago) would have included the just war or nuclear weapons.

What are the dividing lines between Catholic Christians and secularists? Eco (author of Name of the Rose) and Cardinal Martini (in the Catholic corner) discuss four issues: abortion, why women cannot be ordained, hope and the future of mankind and the basis of ethics. Perhaps not the burning issues that many today would think need to be answered, but this book was written in the context of the impending millennium where some predicted this would bring in the end of civilisation as we know it. Today the burning issues would be child abuse, homosexuality, Darwinism or even the environment. Perhaps another age (not too long ago) would have included the just war or nuclear weapons.

After I had read The Thread by Victoria Hislop (see

After I had read The Thread by Victoria Hislop (see