The Armenian Genocide

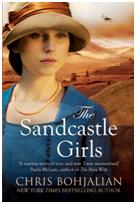

After I had read The Thread by Victoria Hislop (see review), my appetite for history was whetted, especially for history connected with the fall of the Ottoman Empire. So I searched out this book, which then had only just been published. And now what can I say about the book?

After I had read The Thread by Victoria Hislop (see review), my appetite for history was whetted, especially for history connected with the fall of the Ottoman Empire. So I searched out this book, which then had only just been published. And now what can I say about the book?

The Armenian genocide, which even now the Turkish government denies happened. The story centres on a young American aid worker, Elizabeth Endicott, who has gone to Aleppo in Syria as part of an aid mission, and Armen Petrosian, an Armenian engineer who has lost his wife and daughter to the deportations. The barbarity and cruelty of the fading days of the Ottoman Empire are chilling. Some of the worst scenes are seen through the eyes of Elizabeth. I scarcely breathed as the horrific landscape unfurls before the reader. The deportees are women with a few children who are herded from town to town before being left in the “Resettlement Camps”. These camps have no facilities. No food, no shelter, no water. Just guards at the perimeter. They are a place to die, slowly. Suddenly the Turks make the Nazis with their death camps look almost humane, at least they killed their victims, and only removed their clothes just before they died. These Armenian deportees were all naked. All were starving, skeletal figures. The aid that Elizabeth and her father have brought is but a drop in the ocean. The hopelessness of their mission seeps through the pages and stains the soul. The Turks were hell bent on wiping every single Armenian from the face of the earth. The estimate of the number of people kill in the genocide varies – Bohjalian puts it at 1.5 million.

My husband asked why on earth I would want to read such a book? Because it was not all gloom. Little rays of hope. Elizabeth’s efforts could not save a race, but she did what she could to save Nevart, the wife of a doctor and one of the naked deportees that Elizabeth first meets, together with Hartoun, a little girl who has witnessed the brutal death of her family. There is the Turkish doctor, a Muslim, who works tirelessly to bring relief to all including Armenians, the market stall keeper who has watched Hartoun with fondness since she arrived in Aleppo. And also the story of Armen’s survival fighting for the allies against the Turks and the Germans.

Did I enjoy the book – I don’t know. I know that the images will haunt me forever. Often when I was reading it, I longed for the lightness of touch that Hislop bought to The Thread. Bohjalian intersperses the grimness of the mission to Aleppo with the story of Elizabeth and Armen’s grand-daughter as she slowly unravels the story of her grandparents past. This was necessary to give the reader a breather before the horror is continued.

Reading a good novel should be a life changing experience. This book certainly was. But the sad thing is that barbarism, that disdain for the sanctity of human life is still rife in what used to be the Ottoman Empire as we watch Syria descend into civil war.